Last year will go down in the books like 2019 did – an unprofitable year for carriers with the usual twists and turns. Unlike 2019, though, we have not seen anywhere near the level of carrier bankruptcies reported despite the number of long-haul carriers exiting the market.

To put 2023 into context, we must go back five years and start with the 2018 bull market

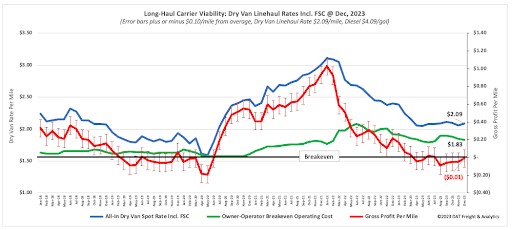

The first half of 2018 was an excellent year for carriers, especially flatbed ones, boosted by a robust industrial economy, rising oil prices, and significant rebuilding efforts following hurricanes Irma and Harvey in late 2017. Changes in the tax code also benefited carriers that placed a record number of orders for new trucks later that year. Owner-operators and small fleet carriers made, on average, $24,000 gross profit (see Figure 1) after all expenses were considered during that year; by all accounts, it was a good year in trucking.

Fig. 1: Long-haul owner-operator viability analysis

As demand cooled in 2019, the industry became increasingly oversupplied, as new trucks hit the road following the frenzied buying spree of new trucks and trailers six to nine months earlier. Downward pressure on spot rates ensued, resulting in many bankruptcies in the second quarter of that year, including some mega-carriers – Falcon, Celadon, and New England Motor Freight (NEMF).

According to Donald Broughton of Broughton Capital LLC, “Approximately 640 carriers went out of business in the first half of 2019, up from 175 for the same period last year and more than double the total number of trucker failures in 2018.”

The net result was a poor financial year for carriers in 2019; average gross profit levels dropped into negative territory. Compared to 2018, when small carriers netted an average of $24,000, 2019 saw carriers lose an average of $2,000 gross profit for the year.

The first quarter of 2020 continued much like 2019, with carriers shedding capacity to match declining freight demand. That was until March 11, when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic.

The pandemic was unprecedented, but so was the long-term impact on trucking

The pandemic upended the freight market – demand crashed, drivers sat idle, consumers of freight hunkered down at home, increasing their spending on e-commerce, and carriers took advantage of whatever financial assistance they could get to weather the storm.

When the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan applications stopped mid-year, the freight market recovered as demand returned, and most carriers came off the sidelines.

What happened in the last six months of 2020 was nothing short of remarkable and set the stage for an unprecedented doubling of for-hire truckload capacity in 2021. From June to December 2020, two things happened that kick-started one of the most profitable 18-month periods in trucking history:

- In the second half of 2020, diesel costs dropped 23% or $0.71/gal, bottoming out at $2.37/gal.

- Over the same timeframe, dry van linehaul rates increased almost $1.00/mile – from $1.85 to $2.80/mile or an increase of 51% by the end of the year.

The spread between fuel and spot rates created higher margins and long-haul capacity doubled throughout 2021 as carriers made record profits and paid down debt. Toward the end of 2021, long-haul carriers made upwards of $1.00/mile gross profit – or the equivalent of $100,000 annually after all costs were considered. The 2023 freight market still felt the effects of this, as carriers exited the market at a much slower pace than most expected.

Carriers of all sizes used the boom to sell excess equipment and property, building massive war chests compared to previous years. They also became more selective of the loads on offer from brokers and, throughout 2021, ran 10,000 fewer miles, averaging 85,000 miles for the calendar year, according to Todd Amen at ATBS. Amen told DAT Freight & Analytics in late 2022, “For the first time, we’re seeing carriers electing to sit the market out as diesel prices spiked over the summer, something we’ve never seen before.”

For some, the runway was nearing the end

All of that changed, though, when Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb 24, 2022, sending diesel prices sky-high and global demand in the opposite direction. By then, many carriers had seen the writing on the wall and were already getting out, realizing the good times of 2021 were in their rear-view mirror. For others, surging diesel prices and falling spot rates meant they realized they were no longer viable.

There was an exodus of carriers in April and May as spiking operating costs resulted in them being unable to pay their bills.

For long-haul carriers, 2022 ended up a mixed year, which started great but gradually deteriorated due mainly to diesel prices reaching a record high of $5.81/gal in June. Another wave of carrier exits followed in September because those carriers struggled to afford their monthly fuel and finance bills.

Despite this, carriers still made a $41,000 gross profit in 2022, around half what they made a year earlier. The carriers that remained in the long-haul sector were drawing down heavily on the cash reserves amassed in 2021, and for most, those reserves were running out as the perfect storm of low rates and high fuel costs gripped the late 2022 freight market.

2023, and the predictable rainy day arrives

Following the massive build-up of shipper inventories in 2021 and 2022 and decreasing freight demand over the year, carriers could still break even in 2023 despite the rollercoaster ride of diesel prices. From the end of January to Independence Day last year, diesel prices fell by 18%, or $0.84/gal, a welcome reduction in operating costs of approximately $0.08/mile, allowing many carriers to stay in the industry a little longer as rates continued to fall.

In the ensuing 10 weeks, diesel shot up 23%, or $0.86/gal, erasing the prior six-month decline and resulting in the third-highest number of carriers exiting the industry in October. Since then, diesel prices have dropped nearly 15%, or $0.70/gal, slowing the rate of carrier exits.

The 2023 freight market ended with more trucks than loads. Despite this, long-haul carriers broke even by year-end after making the equivalent of $3,000 annual gross profit in the first half of 2023 but losing the same amount in the year’s second half.

Compared to the second half of 2019, the second half of 2023 was almost identical, with carriers in negative profit territory for much of it. Most long-haul carriers were getting by but needed to generate more profit to survive long-term or be able to pay for significant repairs. Many are still only a major breakdown away from going out of business.

2024, a turning point

We start 2024 with the market capacity rebalancing and carriers exiting the market, albeit slower than a year ago. Surprisingly, carriers continue to join the industry, fulfilling the American Dream of starting their own businesses. If they can survive the first quarter of this year – when rates are sure to drop along with freight demand – they will thrive when the market turns, hopefully in the Spring.

One thing is for sure: fewer trucks will be available to move a higher freight volume when the freight market does turn. And that means higher freight rates and improved profit margins.

The good times should return this year, unlike the 2021 boom. It will be more like what we saw in 2018.