Van rates subtracted two cents from the national average on Tuesday, dropping it from $1.71 to $1.69/mile. That’s the usual pattern, although last week rates gained on Tuesday (more on that later).

The van national average rate typically declines on Tuesdays, because a higher percentage of trucks are returning from trips that started on Sunday or Monday. The most common length of haul is between 250 and 550 miles for intercity freight. If those trucks started the week in the headhaul direction, they’re going to be offered a backhaul rate to return home. Of course, they could take a lane that is neither headed home or outbound. I call those intermediate lanes. The trend generally, though, is higher for Monday’s loads and lower for Tuesday’s loads, hence I’ve taken to calling it “Backhaul Tuesday.”

I realize that many truckers object to the whole idea of “headhaul” and “backhaul” rates, but this is just the reality of spot market freight. When you go back and forth between two locations, there is almost always more demand and higher rates in one direction than the other. Accepting that reality and understanding how the rates behave is a primary key to success as an independent owner-operator.

What was different in the previous week?

On Tuesday, May 2, rates didn’t fit the usual pattern. Why not? One word: weather. For the past few weeks, we have seen disruption in many of the most active states due to tornadoes, thunderstorms and flooding. This resulted in road closures which impacted major freight markets in Oklahoma, Kansas, Arkansas, Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee during the final week of April which usually sees a spike in demand. The news was filled with scenes of flooding and tornado damage. As May kicked off, most roads were clear, and the pent-up demand drove rates up to start the new month.

Meanwhile, there are signs of frenetic activity in areas that were not affected by the weather. Houston and Atlanta are pumping out freight like crazy. Also, Atlantic seaports of Jacksonville, Savannah, and North Charleston are driving strong numbers. Meanwhile, loads from southern California are climbing after a couple soft years. These changes signal that the second quarter will bring stronger revenues for carriers and brokers alike. We’ll see how this plays out in the next few weeks, but I expect an increase in freight volume and rates from now through the end of June.

How to make more money in this environment

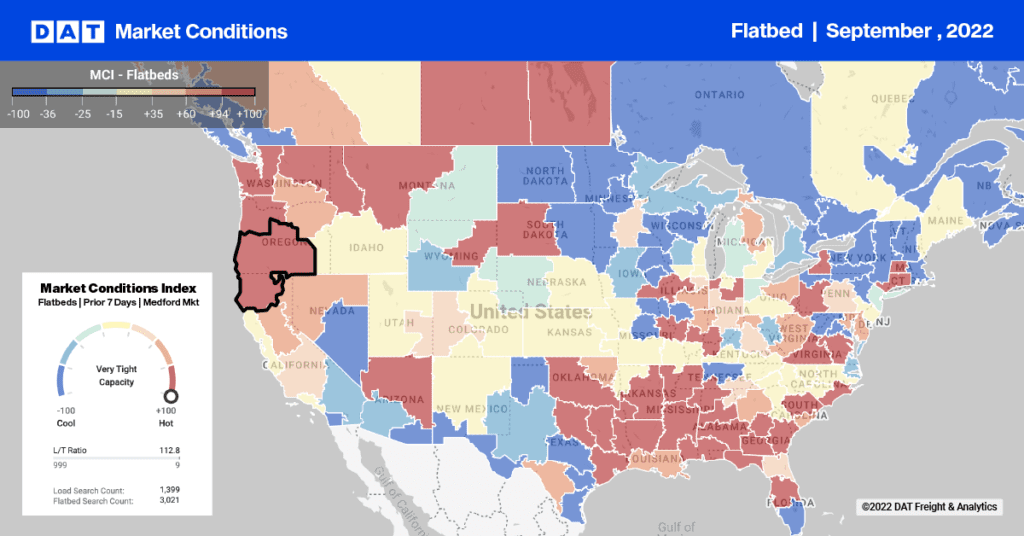

When rates are trending up, truckers can maximize revenue by planning roundtrips in advance. Look at Hot Market Maps in DAT Power or DAT RateView, and try to find a load into a “hot” market — or better still, try to find loads that go back and forth between two hot markets. A hot market has a lot more loads available than trucks, so carriers face less competition. If you find a roundtrip that works for you, ask the load providers if they have regular freight on those routes, and see if you can negotiate a recurring weekly haul. If you want to keep your truck moving all week, you can develop routes that go from one destination to another, in a triangular (TriHaul) or rectangular route. If you plan well, you may be able to move three or four consecutive loads in the headhaul direction.

For brokers, look at DAT RateView for lanes where there’s a big gap between the current average contract rate and the spot market rate. Look for a shipper that needs your services, preferably on a recurring basis. Then find a carrier — or more than one — who will commit to those hauls. By focusing and bidding on those lanes as often as you can, you’ll be able to price your services competitively to the shipper while continuing to offer the carrier an attractive rate.

Find loads, trucks and lane-by-lane rate information in the DAT Power load board, including rates from DAT RateView.