We’re a few weeks away from the official start of winter, but we’re already seeing the annual shift in produce farming to warmer southern latitudes. At the start of December, the number one domestically produced commodity being hauled by truckload carriers is, not surprisingly, potatoes (18% of weekly volume). After all, it is harvest season in Canada’s Alberta Province, as well as in Colorado, Idaho, Washington, and Wisconsin. Rounding out the Top 5 commodities are apples (12%), tomatoes (7%), dry onions (7%), and lettuce (6%), but they all come from different regions where each has distinct growing seasons.

Get the clearest, most accurate view of the truckload marketplace with data from DAT iQ.

Tune into DAT iQ Live, live on YouTube or LinkedIn, 10am ET every Tuesday.

Apples are primarily harvested in the Pacific Northwest (PNW), Florida, and New York State, while almost 65% of tomato production comes from Mexico at this time of the year. Most of that volume enters the U.S. at Pharr, Texas, in the McAllen freight market. Onions come primarily from the PNW, with lettuce originating in Arizona and California, also known as the U.S. Salad Bowl.

Bananas are not grown commercially in the U.S. and are, far and away, the biggest fruit seller in grocery stores. Just over 80% of banana imports come from Central and South America (Guatemala 45%, Costa Rica 15%, Ecuador 12%, and Honduras 10%), with almost 40% landing in the Philadelphia and Delaware ports.

Knowing when and where produce originates is a key to understanding the demand for temperature-controlled freight over the quieter winter months.

The winter salad bowl

One of the more fascinating logistical moves occurs around this time of the year: the shift in production and processing of leafy greens from California’s Salinas Valley, or America’s Salad Bowl, to the desert region in southeast California and southwest Arizona. The major freight market for this produce is Yuma, Arizona. According to the Arizona Farm Bureau, the area near Yuma transforms into the “Winter Salad Bowl,” producing almost all vegetables (lettuce, broccoli, kale, and cauliflower) consumed in the United States during winter.

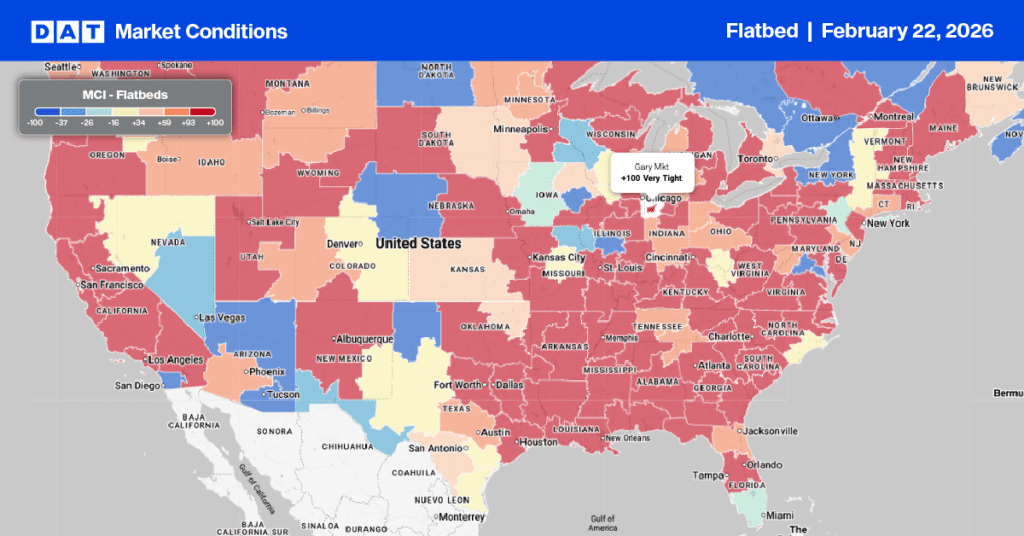

Each year, beginning in mid-to-late November, Church Brothers Farms in Salinas, CA, relocates its entire lettuce production facility to Yuma. This year, the move occurred in 53 hours, using around 60 flatbed trucks for the 575-mile haul. For truckload carriers, this means leafy green volumes drop off in Salinas and begin to increase in Yuma between November and March before transitioning back to California in the Spring.

Yuma, AZ, the sunniest city in the world

According to Guinness World Records, the fertile, well-irrigated land in the Colorado River lowland and Yuma’s status as the sunniest city in the world make it ideal for year-round farming. Farmers can grow two, and sometimes three, crop rotations on the same plot of land in a year. This region is also a desert, as it receives only three inches of rain a year, making the nearby Colorado River critical to farming.

The shift in produce-growing regions can also come at a cost for truckload carriers. Yuma is 238 miles from Ontario, CA, 184 miles from Phoenix, and 175 miles from San Diego, the nearest large inbound freight market. Getting to Yuma without an inbound load could cost carriers around $500 in operating costs before picking up the outbound leafy green load. The cost of such a move must be factored before accepting the load in the first place.